Revused Jaunary 19, 2001

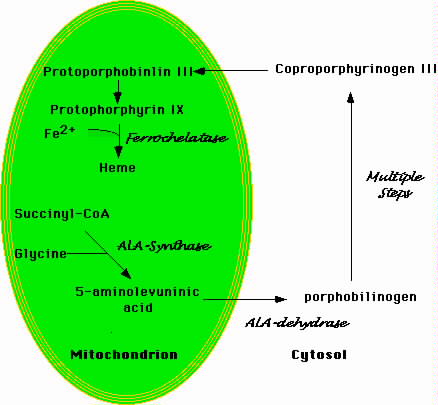

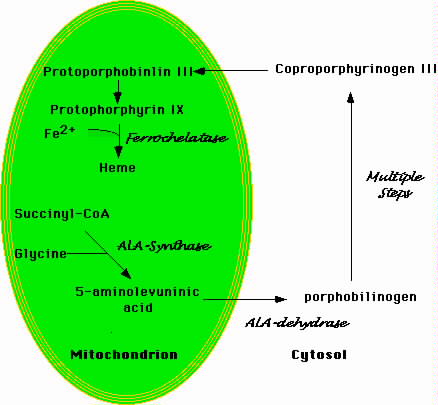

Figure 1.Schematic Representation of Heme Biosynthesis

|

| Heme biosynethsis begins in the mitochondrion with the formation of 5-aminolevulinic acid. This molecule moves to the cytosol where a number of additional enzymatic transformations produce coproporphyrinogin III. The latter enters the mitochondrion where a final enzymatic conversion produces protophorphyrin IX. Ferrochelase inserts iron into the protophorin IX ring to produce heme. |

Mitochondria are the source of the oxidative phosphorylation that provides most of the ATP used by eukaryotic cells. The mature erythrocyte is the sole mammalian cell that lacks mitochondria and relies totally on glycolysis as an energy source. Most cells contain between 100 and 300 mitochondria (Jaussi, 1995). Mitochondria are semi-autonomous organelles that likely began as freestanding prokaryotes that invaded eukaryotic cells more than a billion years ago (Jansen, 2000). A symbiotic relationship eventually developed between these prokaryotic cells and their eukaryotic hosts. The former prokaryotes lost the capacity for independent existence but became indispensible to the eukaryotic cells.

Mitochondria retain vestiges of their former independent life. Most importantly mitochondria have small DNA genomes (about 16 kb) and replicate independently within their host cells. Mitochondrial DNA retains many features of prokaryotic genomes, including a circular structure lacking introns (Boore, 1999). The mitochondrial genome encodes a small number of proteins as well as several transfer RNA molecules. Mitochondrial DNA lacks chromatin and the organelles have a limited capacity for DNA repair. These characteristics mean that mutations in the mitochondrial genome that produce sideroblastic anemia likely will remain uncorrected.

Mitochondria replicate independently of the nuclear genome (Kuroiwa, 2000). When cells undergo mitosis, mitochondria distribute stocastically to the daughter cells. Acquired mitochondrial defects therefore pass unevenly to the daughter cells. This property is important to the some of the hereditary mitochondrial disorders that produce sideroblastic anemia. This characteristic also poses a conundrum with respect to the acquired sideroblastic anemias. A few cases of sideroblastic anemia associated with myelodysplasia have acquired mutations that impair function of some cytochromes (see below). The mutation presumably began as an alteration in a single mitochondrion. The puzzling question is how mitochondria with impaired enzymatic function come to predominate in the cells. Each mitochondrion has several genomes (i.e., several circular DNA molecules), and each cell has several hundred mitochondria. Logically, the defective mitochondrion should be at a survival disadvantage. The acquired sideroblastic anemias remind us that much remains to be learned about the physiology of these fascinating organelles.

Figure 1 is a simplified schema of heme biosynthesis. The process begins in the mitochondrion with the condensation of glycine and succinyl-CoA to form delta-amino levulinic acid (ALA) (Bottomley et al, 1988). Pyridoxal phosphate is a cofactor in the reaction. ALA then moves to the cytoplasm where several additional enzymatic transformations produce coproporphyrinogen III. This molecule enters the mitochondrion where additional modifications, including the insertion of iron into the protoporphyrin IX ring by ferrochelatase, produce heme. Defects in the cytoplasmic steps of heme biosynthesis cause various forms of porphyria. Functional abnormalities of the enzyme porphobilinogen deaminase, for instance, produce acute intermittent porphyria (Mustajoki et al, 2000).

In contrast, defects in the steps of heme biosynthesis that occur within the mitochondrion produce sideroblastic anemias. For instance, perturbations of the enzymatic activity of delta-amino levulinic acid synthase (ALAS) produce sideroblastic anemia (Bottomley et al, 1992). The X-linked hereditary sideroblastic anemias result from mutations in the gene encoding ALA-S. Isoniazide, a drug used to treat Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and that commonly produces sideroblastic anemia in people who fail to use pyridoxine prophylaxis, directly impairs ALAS function (Yunis et al, 1980). A group of disorders termed "mitochondrial cytopathies" result from deletions of portions of the mitochondrial genome (Buemi et al, 1997). The consequent profound mitochondrial dysfunction produces sideroblastic anemia in some of these disorders. The best known of these is Pearsonís syndrome, which was the first characterized entity in this class of disease (Pearson et al, 1979).

Most commonly, the sideroblastic anemias are classified as hereditary

or acquired conditions (Table 1). Most of the hereditary forms are X-linked,

although some family studies have revealed autosomal dominant or autosomal

recessive modes of transmission (Cox et al, 1990). In many instances,

isolated cases of congenital sideroblastic anemia defy classification as

they lack the well-documented pedigrees needed to firmly establish modes

of transmission (Dolan et al, 1991).

Table 1. Classification of Sideroblastic Anemias

|

|

|

|

| Hereditary | Congenital X-linked | ALAS-2 mutations

Xp11.12 linked disorders |

| Autosomal dominant | Unknown | |

| Autosomal recessive | Unknown | |

| Mitochondrial Cytopathy | mtDNA

Chromosome 4p16 abnormality |

|

| Acquired | Myelodysplasia | mtDNA point mutations, and unknown |

| Drugs | Ethanol, INH, chloramphenicol, cycloserine | |

| Toxins | Lead, zinc | |

| Nutritional | Pyridoxine deficiency, copper deficiency |

The frequency of the acquired sideroblastic anemias far exceeds that of the hereditary varieties. Drugs and toxins lead this category, propelled largely by the high frequency of alcohol abuse in many societies (Larkin et al, 1984). Alcohol produces sideroblastic anemia in only a small fraction of people. A large number results, however, when this small fraction is factored against the very large number of alcohol abusers. The next largest subgroup is itself a subset of the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) (Hast, 1986). Rarely, nutritional imbalances or other insults (e.g. hypothermia) produce sideroblastic anemia (O'Brien et al, 1982).

The exact mechanism by which disturbed heme metabolism produces sideroblastic anemias remains elusive. Heme is an essential component of many mitochondrial enzymes (cytochromes b, c1, c, a, a3) as well as cytosolic enzymes such as catalase. The molecule is also an integral component of hemoglobin where it has both structural and functional roles. Heme modulates translation of globin mRNA, stabilizes the globin protein chains, and mediates reversible oxygen binding.

ALAS is both the first and the rate-limiting enzyme in heme biosynthesis (Bottomley et al, 1988). Heme modulates its activity through feedback inhibition. The two genes that encode ALAS have been cloned and assigned chromosomal locations. The gene that encodes ALAS-1 (also called ALAS-n) exists on chromosome 3 (3p21) (Bishop et al, 1990). This ubiquitous enzyme is particularly abundant in the liver. ALAS-1 provides the basal heme production needed by all cells and maintains a relatively stable level.

The enzyme directly relevant to sideroblastic anemia is ALAS-2 or ALAS-e. A gene on the X chromosome (Xp11.21) encodes this enzyme, whose expression is restricted to the erythroid lineage (Cotter et al, 1992a). In addition to heme-mediated feedback inhibition of enzymatic function, ALAS-2 is a member of a small family of genes whose expression is modulated by iron (Cox et al, 1991).

The best-characterized genes of this family are those encoding ferritin and the transferrin receptor (Klausner et al, 1989). Ferritin mRNA contains a conserved stem-loop sequence in the 5í-untranslated region called the iron response element (IRE). A homologous sequence exists in the 5í-untranslated region of the ALAS-2 message. In contrast, transferrin receptor mRNA has five IRE elements all in the 3í-untranslated region.

Two cytoplasmic proteins called the iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 (IRP1 and IRP2) bind to the IRE regions of the messenger RNA. In the absence of iron, IRP1 binds to the IRE elements in the 5í-untranslated regions of the messages encoding ferritin and ALAS-2. The IRE/IRP complex blocks message translation, lowering the biosynthesis of ferritin and ALA-2. This response makes teleological sense. In the absence of iron, the cell does not need the iron storage protein, ferritin. Similarly, in the absence of iron, erythroid precursors dampen production of ALAS-2, with a consequent diminution in protoporphyrin IX synthesis. Without iron, the cells need not produce protoporphyrin IX since conversion of this molecule to heme is impossible.

A defect in the ALAS-2 IRE theoretically could produce a sideroblastic anemia. A mutation that makes the IRE a high affinity target for the IRP proteins irrespective of ambient iron concentrations, for instance, would substantially lower the level of ALAS-2 in the cells. No such defect has been described, however. This contrasts with ferritin, where abnormal IRE elements in the message produce a familial syndrome of serum hyperferritinemia and associated cataracts (Beaumont et al, 1995). Since ALAS is an enzyme, extreme defects in its production might be required to produce clinical syndromes. Changes in enzymatic activity might compensate for lesser perturbations in enzyme level.

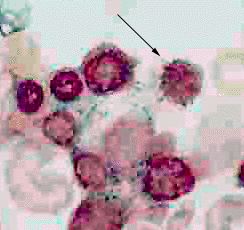

The signal feature of sideroblastic anemia is mitochondrial iron deposition

(Koc et al, 1998). High resolution microscopy of cells stained with

Perlís Prussion blue usually demonstrates one to four siderocytes throughout

the cytoplasm of normoblasts. Large clusters of siderocyte bodies encircle

the nucleus of ring sideroblasts (Figure 2). Ring sideroblasts usually

constitute at least 15% of the normoblasts, and the figure often reaches

50%.

|

| The bone marrow aspirate from a patient with sideroblastic anemia in this photomicrograph was stained with Perl's Prussian blue. The arrow indicates a normoblast with a greenish halo of material stained by Perl's Prussian blue surrounding the nucleus. Electron microscopic examination would should these to be iron-laden mitochondria. |

Electron microscopy shows crystalline iron deposits in the cristae of the mitochondria (Grasso et al, 1969). The basis of this phenomenon is unknown. Simple cellular iron overload is not the answer. Massive cellular iron overload occurs in both hereditary and transfusional hemeochromatosis. Iron laden mitochondria are manifest in neither disorder. Sideroblasts show normal iron uptake, but subsequent poor incorporation into heme (May et al, 1982). Mishandling of iron by mitochondria could be the basis of the iron deposits. Our limited understanding of mitochondrial iron metabolism has precluded testable hypotheses, however.

Mitochondrial iron deposits might be more than a morphological curiosity.

Iron catalyzes the formation of reactive oxygen species through Fenton

chemistry (Liochev et al, 1994). Molecules such as the hydroxyl

radical (ïOH) arise in settings where oxidation reactions occur in proximity

to iron (Gutteridge et al, 1991). The oxidative metabolic machinery

of the mitochondrion makes it an ideal site for the generation of reactive

oxygen species. The primary damage that produces iron-laden mitochondria

in sideroblastic anemia could produce a feedback loop of escalating mitochondrial

injury. The hydroxyl radical, for instance, promotes lipid and protein

peroxidation as well as cross-links in DNA strands. The latter phenomenon

could be particularly injurious given the dearth of DNA repair enzymes

in mitochondria.

Missense mutations of the ALAS-2 gene produce most cases of X-linked sideroblastic anemia (Cotter et al, 1992b; Bottomley et al, 1992; Cox et al, 1992; Edgar et al, 1997; Cox et al; 1994). Years after their initial evaluation, investigators located several members of the pedigree originally described by Cooley and analyzed their DNA using current techniques in molecular biology (Cotter et al, 1994). These now adults indeed had missense mutations involving the ALAS-2 gene. Rarely has anyone correctly described two major disorders that withstood the rigors of subsequent scientific investigation by more powerful analytical tools. The other disorder in this instance is, of course, Cooley's anemia, now known as ß-thalassemia major (Cooley et al, 1927).

The mutations of the ALAS-2 gene can be classified according to their effects on the enzyme product: low affinity for pyridoxal phosphate, structural instability, abnormal catalytic site, or increased susceptibility to mitochondrial proteases. Any of these abnormalities decrease the biosynthesis and/or activity of ALAS and consequently lower heme production. The net result is low hemoglobin production by the developing normoblasts and anemia. Ineffective erythropoiesis results from the imbalance between heme biosynthesis and globin chain production.

Hereditary X-linked sideroblastic anemia usually occurs in males, of course. Cases involving females in a pedigree derive most often from skewed lyonization patterns in the affected girls (Seip et al, 1971; Dolan et al, 1991; Seto et al, 1982; Buchanan et al, 1980). Bottomley and colleagues presented an abstract describing three unrelated families in which females had clinical features of hereditary sideroblastic anemia. Curiously, no affected male existed in the pedigrees. DNA sequencing confirmed ALAS-2 gene mutations on the X chromosome. Skewed lyonization explained the clinical symptoms in the probands. In one pedigree, the mother and one sister of the proband were unaffected carriers because they did not have skewed lyonization patterns. The absence of affected males suggested to the investigators that the hemizygous state for the mutations produced an embryonic lethal situation. No follow-up report to this intriguing observation exists.

Jardine and colleagues described congenital sideroblastic anemia in a brother and a sister born to unaffected parents, making likely autosomal recessive transmission (Jardine et al, 1994). The ALAS-2 enzymatic activity in the erythroblast fraction of the marrow was normal. Genetic analysis excluded ALAS-2 gene mutations as the cause of the sideroblastic anemia. The investigators hypothesized that an autosomal gene regulates ALAS-2 gene expression. A defect in this ALAS-2 regulatory gene would produce sideroblastic anemia as a downstream event. The fact that ALAS-2 enzymatic activity was normal in the erythroblast fraction, however, means ALAS-2 gene expression was not the problem. A defect that prevented ALAS-2 localization to the mitochondria would produce sideroblastic anemia. ALAS-2 production and enzymatic activity would be normal, as the investigators found. Sideroblastic anemia would result from a deficiency of ALAS-2 in the mitochondria. Unfortunately, the investigators did not examine the subcellular localization of ALAS-2.

In 1979, Pearson and colleagues described children from several unrelated families who manifested sideroblastic anemia and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction (Pearson et al, 1979). Subsequent cases of what is now called Pearsonís syndrome also had varying degrees of lactic acidosis, hepatic and renal failure. Bone marrow examination showed in addition to the ring sideroblasts, large vacuoles in the erythroid and myeloid precursors. Few of the probands survived past early childhood.

The disorder results from mitochondrial DNA deletions that often are as large as 4 kb (Cormier et al, 1990). Southern blots of mitochondrial DNA show genomes of normal size along with the truncated DNA. Variation in the intensity of the two bands reflects mitochondrial heteroplasmy in the mother and offspring (Bernes et al, 1993). These deletions impair the biosynthesis of various components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain critical to mitochondrial function. Other disorders result from deletions of different portions of the mitochondrial genome (e.g., myopathy, encephalopathy, ragged red fibers [in muscles] and lactic acidosis, or MERRL). Sideroblastic anemia is not part of the clinical spectrum of these syndromes.

An instructive form of sideroblastic anemia occurs in patients with Wolframís syndrome (DIDMOAD; diabetes insipitus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness) (Borgna-Pignatti et al, 1989). The condition results from large deletions of the mitochondrial genome. The heteroplasmic nature of the mitochondrial defect in Wolframís syndrome is typical of a mitochondrial cytopathy (Rotig et al, 1993). The anemia in affected individuals results from both sideroblastic and megaloblastic derangements in erythroid maturation.

Unlike Pearsonís syndrome and other mitochondrial cytopathies, Wolframís

syndrome shows an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Family studies

point to a nuclear gene on chromosome 4 (4p16) as the cause of Wolframís

syndrome (Barrientos et al, 1996). The current hypothesis holds

that the gene on chromosome 4 contributes somehow to the stability of the

mitochondrial genome. Without the function of this still unidentified gene,

mitochondrial DNA falls victim to damage that ultimately produces large

deletions. Impairment of energy production and other mitochondrial functions

produce the sideroblastic/megaloblastic anemia, along with the other ultimately

deadly defects in this disorder.

Acquired sideroblastic anemias are much more frequent than the hereditary

forms. The defect sometimes surfaces in the context of a myelodysplastic

syndrome. Other instances of acquired sideroblastic anemias reflect exposure

to toxins or deficiencies of nutritional factors. The hereditary sideroblastic

anemias nearly always manifest in childhood or infancy. In contrast, the

acquired forms, particularly those associated with myelodysplasia, nearly

always occur in older adults.

A variety of metabolic abnormalities can evolve in the abnormal stem cells, including defective anchoring of phosphotidylinositol-linked membrane proteins (i.e., PNH), hemoglobin H production, and ring sideroblasts (Hillmen et al, 2000; Yoo et al, 1980). Investigators often viewed the acquired sideroblastic anemia associated with myelodysplasia as a monolithic entity, dubbed refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS). Closer inspection reveals that certain morphologic and chromosomal features predict significant differences in the clinical course of patients with sideroblastic anemia (Gattermann et al, 1990).

One subset of patients has dysplastic features confined to the erythroid series. Chromosomal abnormalities occur in some people, but usually are relatively selective with defects such as the 5q- anomaly. This condition has been named "pure sideroblastic anemia" (PSA). In the absence of myeloid or platelet abnormalities, anemia dominates the clinical course. The need for frequent transfusion produces iron overload that can impair cardiac function and injure the liver. With adequate chelation therapy, these patients can survive and even thrive for many years. Most importantly, very few patients develop acute leukemia.

The second group of patients has abnormalities in all three cell lines in addition to ring sideroblasts. Chromosomal abnormalities are prominent and often include multiple deletions, trisomy, or inversions. Although the anemia is troublesome, neutrophil and platelet abnormalities are the dominant problems for these patients. Infection is the most common cause of death, due both to neutropenia and neutrophil dysfunction. Bleeding is a common problem due to thrombocytopenia and/or platelet dysfunction. As many as 15% of patients who survive these problems develop an acute leukemia that often is refractory to treatment. The prognostic implications of these two forms of sideroblastic anemia associated with myelodysplasia make mandatory detailed morphological and cytogenetic evaluation at the time of diagnosis.

The ring sideroblasts associated with myelodysplastic syndromes manifest in both the early and late erythroid precursors. This contrasts with the hereditary X-linked conditions in which prominent sideroblastic rings generally appear only in the more differentiated normoblasts. Only recently, have investigators pinpointed some of the abnormalities that might explain the ring sideroblasts associated with myelodysplasia. The greatest likelihood is that a plethora of defects exists, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of myelodysplasia and its associated sideroblastic anemia.

Gattermann and colleagues described at least two point mutations in mitochondrial DNA of patients with acquired sideroblastic anemia (Gattermann et al, 1997). One mutation was a T to C change at nucleotide 6742 of the mitochondrial genome. The affected gene encodes cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1. The mutation produced an aberrant protein in which a threonine residue replaced isoleucine at residue 280. The other mutation also involved a T to C transition, this time at nucleotide 6721 of the mitochondrial genome. The defect again altered cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1, resulting in a change from methionine to threonine at residue 273.

The fact that mitochondria from other tissues of these patients showed no abnormality was consistent with an acquired defect solely involving the hematopoietic stem cells. Further investigation proved these mutations to be heteroplasmic. That is, the affected cells have a mixture of normal and mutant mitochondria.

Technical limitations precluded analysis of mitochondrial function in samples derived directly from the patients. The investigators therefore performed experiments using an artificial construct (Broker et al, 1998). They used Rh-0 cells from the immortalized cell line 143B as the starting material. Rho-0 cells are selected to have no functioning mitochondria through repetitive treatments with ethidium bromide followed by low-level ultraviolet irradiation. The investigators fused platelets from the affected patients with the Rho-0 143B cells, which then contained patient mitochondria (platelets were used because they contain mitochondria but no nuclear DNA). The heteroplasmic nature of the mitochodrial defect in the patients allowed the investigators to select clones that contained only mutant mitochondria and clones that contained only wild-type mitochondria.

No difference in the growth characteristics existed between the normal and mutant reconstituted Rho-0 143B cells. Differences in respiration between the reconstituted wild-type and mutant mitochondria cells were modest at best. Equivocal results and a convoluted testing system prevent a firm statement about mitochondrial function and its relationship to the sideroblastic anemias. The same group of investigators reported another mitochondrial DNA mutation that affected one of the mitochondrial transfer RNAs (Gattermann et al, 1996). The functional consequence, if any, of the mutation is unknown.

|

Isoniazid frequently causes sideroblastic anemia (Sharp et al, 1990). Pyridoxine prophylaxis is part of treatment regimens involving the drug in order to prevent this complication. Isoniazid-induced sideroblastic anemia caused a number of deaths before investigators made the connection between the drug and the severe sideroblastic anemia. The drug markedly inhibits ALAS activity (Pasanen, 1981).

Chloramphenicol inhibits mRNA translation by the 70S ribosomes of prokaryotes. The drug does not affect 80S eukaryotic ribosomes. The majority of mitochondrial proteins are encoded by nuclear DNA and are imported into the organelles from their site of synthesis in the cytosol. Mitochondria retain the capacity to translate a few proteins encoded by the mitochondrial genome on indogenous ribosomes. True to its prokaryotic heritage, mitochondrial ribosomes are similar to those of bacteria, meaning that chloramphenicol inhibits protein synthesis by these ribosomes. Chloramphenicol-induced sideroblastic anemia is believed to result from this inhibition. Animal studies have documented diminished ALAS and ferrochelatase activity in cases of sideroblastic anemia secondary to chloramphenicol intoxication (Rosenberg et al, 1974).

More recently, Leiter and co-workers examined the effects of chloramphenicol on cellular iron metabolism using the human erythroleukemia cell line, K562 as a model system (Leiter et al, 1999). As expected, chloramphenicol inhibited oxidative metabolism, reduced the activity of cytochrome c oxidase, and lowered the ATP content of the cells. Chloramphenicol also markedly reduced the production of ferritin and the transferrin receptor by the cells. The effect was surprising since the eukaryotic ribosomes in the cytosol are sites of synthesis of these two iron-related proteins. Chloramphenicol did not inhibit the synthesis other cytoplasmic or membrane proteins of the cell. The investigators concluded that the previously unsuspected link between mitochondrial function and cellular iron metabolism might contribute to the microcytic, hypochromic anemia that often develops even in the absence of sideroblastic changes in the bone marrow.

Lead intoxication is a particularly insidious cause of sideroblastic anemia (Goyer, 1993). Iron deficiency enhances lead absorption, meaning that the two conditions are often concomitant (Gerson, 1990). Children with lead intoxication more commonly develop sideroblastic anemia than do adults (Balestra, 1991). The basis of the discrepancy is not clear. The diminishing use of lead-based paints has reduced but not eliminated lead as a problem for children. Soil in some regions of the world has an intrinsically high lead content, and the element attains high levels in many plants used for food. Many countries have banned gasoline supplemented with lead. Unfortunately, the ban is not worldwide. Many less affluent countries continue to use gasoline containing lead since it provides more energy per litre and is less expensive than the more highly refined gasoline. Engine emissions deposit lead both in soil and drinking water.

Occasionally, toxic insults to the bone marrow produce sideroblastic anemia. In one report, a patient with chronic myelogeous leukemia developed sideroblastic anemia when placed on busulfan therapy (Fernandez, et al., 1988). The sideroblastic anemia remitted with cessation of the busulfan treatment. One child developed sideroblastic anemia due to antibodies that suppressed erythroid maturation (Ritchey, et al., 1979). IgG purified from the patient's plasma suppressed in vitro growth of erythroid precursors. After no response to a course of steroid therapy, the child achieved a complete remission with a round of immunosuppressive therapy. Other instances of anemia secondary to immunosuppression of erythropoiesis, such as pure red cell aplasia, do not have sideroblastic characteristics. The apparently unique nature of the autoantibiody in the described case remains a mystery.

Finally, overdose of chelators such as penicillamine or triethylene tetramine dihydrochloride (Trientene or TTH) used in treatment of Wilsonís disease can produce sideroblastic anemia. Excessive chelation produces a relative copper deficiency. Copper catalyzes the last step in heme biosynthesis, insertion of iron into protoporphyrin IX. Zinc intoxication has led to sideroblastic anemia in patients using excessive amounts of vitamin supplementation (Porea, et al., 2000). Excessive zinc produces widespread metabolic disturbances, including depressed levels of serum copper. The latter abnormality could be the proximate defect in zinc-induced sideroblastic anemia. Fortunately, the condition reverses with cessation of zinc ingestion.

The role of copper in human iron metabolism is extremely complex (Danks, 1986). Copper enhances intestinal iron absorption, modulates reticuloendothelial activity, facilitates cellular iron uptake from transferrin and promotes iron incorporation into heme. Copper deficiency of all causes (malnutrition, prolonged total parenteral nutrition, gastric surgery, prematurity, zinc supplementation, excessive chelation) can result in acquired sideroblastic anemia (Perry et al, 1996).

The history should include detailed questions concerning possible toxin or drug exposures, since these are reversible conditions. A detailed family history looking for anemia, particularly in male relatives, is important. Most hereditary sideroblastic anemias present in childhood. However, we are now recognizing milder cases of hereditary sideroblastic anemia whose symptoms do not draw attention until adulthood. Severe forms of most diseases are usually the first described. Over time, a broader clinical spectrum with mild or formes furstes of the conditions becomes apparent. No pathognomonic physical finding exists for sideroblastic anemia.

The bone marrow picture in sideroblastic anemia was described earlier. The blood smear sometimes reveals basophilic stippling, hypochromia and microcytosis, although normocytosis and macrocytosis are possible, particularly in myelodysplastic syndromes. A dimorphic red cell population is characteristic of female carriers of the hereditary conditions.

Iron deficiency can coexist with sideroblastic anemia. This scenario is particularly common in patients with myleodysplasia who can have chronic gastrointestinal bleeding due to platelet problems. Iron deficiency can mask sideroblastic anemia. Sideroblastic anemia remains in the differential diagnosis of patients with iron deficiency and anemia that is refractory to iron replacement. A repeat bone marrow following iron replacement can show ring sideroblasts not seen in the initial sample.

Iron overload is more common than deficiency, however, even in patients without a significant blood product transfusion history. The exact cause of iron overload in sideroblastic anemia patients is unclear. Coexisting hemochromatosis gene mutations do not appear to be responsible (Beris et al, 1999). Ineffective erythropoiesis, as occurs with thalassaemia, can accelerate iron absorption from the gut. The ineffective erythropoiesis associated with sideroblastic anemia is much milder and does not completely explain the iron overload. Iron overload is a particular problem for patients with pure sideroblastic anemia. They are less likely to fall victim to the complications produced by myelodysplasia. Consequently, they can live long enough so that problems related to iron overload, including congestive heart failure and cirrhosis, become life-threatening issues.

After obtaining baseline parameters (red cell indices, iron studies), the initial dose of pyridoxine should be 100-200mg daily by mouth with a gradual escalation to a daily dose of 500mg. Folic acid supplementation compensates for possible increased erythropoiesis, should the pyridoxine work. A reticulocytosis occurs within 2 weeks in responsive cases, followed by a progressive increase in the hemoglobin level over the next several months. The maintenance dose of pyridoxine is that which maintains a steady-state hemoglobin level. Microcytosis often persists, but is of no clinical significance.

Except in toxin-induced cases, pyridoxine treatment is usually indefinite. Patient compliance or drug side effects can limit the treatment regimen. Fortunately, side effects are rare with daily doses of less than 500mg. Some patients on doses in excess of 1000mg daily have developed a reversible peripheral neuropathy. In responsive patients, anemia recurs with discontinuation of the pyridoxine.

Many patients with sideroblastic anemia require chronic transfusion to maintain acceptable hemoglobin levels. Patient symptoms rather than an absolute hemoglobin level or hematocrit should guide transfusion. This will limit the adverse consequences of transfusion, which include transmission of infections, allo-immunization and secondary hemeochromatosis.

Even in patients with no meaningful transfusion history, some authorities advocate yearly monitoring of the ferritin level and transferrin saturation. Iron chelation with desferrioxamine is the standard treatment for transfusional hemeochromatosis. Occasionally, patients with a modest anemia (e.g., hemeoglobin=10 g/dL) who are not transfusion-dependent will tolerate small-volume phlebotomies to remove iron. In some cases, the anemia improves with removal of excess iron (Hines, 1976; French et al, 1976). This could reflect a reduction in mitochondrial injury by iron-mediated reactive oxygen species. This is pure speculation, however, and the scenario is distinctly unusual.

Anecdotal reports and small case series describe allogeneic bone marrow

or stem cell transplantation for sideroblastic anemia (Gonzalez et al,

2000; Urban et al, 1992). The obvious advantage is the possibility

of cure, as has occurred in patients with ß-thalassemia.

Possible cure must be balanced against transplant complications, particularly

in older people. Families with severe forms of hereditary sideroblastic

anemia should receive genetic counseling.

Sideroblastic anemias vary in etiology and pathophysiology. The

common thread in these disorders is distinct biochemical abnormalities

affecting heme biosynthesis. Recent discoveries improved our understanding

of the interplay between mitochondrial function, heme biosynthesis, and

cellular iron metabolism. This new knowledge likely will point the way

to improved therapeutic modalities.